Testing Web Components with Karma, Mocha, Chai and TypeScript

Originally published at labs.thisdot.co

Dec 1, 2020 · 9 minutes read · Follow @luixaviles

Imagine yourself building an electric car.

By design, this car has an electric motor, a thermal system(cooling), a battery, a charge port, a transmission, and other units. Every part of the system has requirements that must be met before being attached to the other components.

If any of these components has not been properly tested, it may happen that when testing the whole car it does not work or has faults in its operation.

In the same way, the software can be considered as a collection of units of functionality. The quality of all the system would be determined by the quality of every piece of its implementation.

Unit Tests

Unit tests are functions implemented to verify the behavior of the code under certain scenarios. Let’s suppose we have a function that returns a greeting:

function greeting(name?: string): string {

return name ? `Hello ${name}!` : 'Hello!';

}

Following the TDD approach, you can write your first test with a valid name='Luis' as an input with Hello Luis! expected as a result. However, how could you ensure the correct operation of this function under other parameters? Let’s think in the following cases:

- An invalid situation, where the function receives an empty string or

undefined. - A valid situation, where the function receives a valid name as a string.

Both conditions can be considered part of the same scenario. Then you may define a formal way to write them:

- Scenario: "Greeting Function"

- assert(greeting() == 'Hello!')

- assert(greeting('Luis') == 'Hello Luis!')

In the JavaScript world, there are a lot of options in terms of tools to implement this kind of test. Let’s talk about them in the next section.

Testing Tools for Web Components

Think for a while about the steps you need to perform before starting running unit tests in your JavaScript/TypeScript project.

Most probably you have to think about installing and configuring some tools:

- A Testing Framework, which defines a set of guidelines and rules to implement your test cases.

- A Test Runner, which is the tool that executes your unit tests as a whole suite.

Not only that, it would be great to consider a Web Test Runner to run the JavaScript code and “render” the DOM elements. This point is particularly important to test our web components.

With so many options in mind, it would be easy to lose your way and run out of time. Thus, the open-wc team provides a set of tools and recommendations to facilitate testing tasks.

Setup

You can use the project scaffolding tool to create a new project from scratch. The TypeScript support and common tooling for tests is only one command away:

npm init @open-wc

# Select "Scaffold a new project" (What would you like to do today?)

# Select "Application" (What would you like to scaffold?)

# Mark/Select "Linting", "Testing", "Demoing" and "Building" (What would you like to add?)

# Yes (Would you like to use TypeScript?)

# Mark/Select "Testing", "Demoing" and "Building" (Would you like to scaffold examples files for?)

# my-project (What is the tag name of your application/web component?)

# Yes (Do you want to write this file structure to disk?)

# Yes, with npm (Do you want to install dependencies?)

Next, pay attention to the generated files:

|- my-project/

|- src/

|- test/

|- my-project.test.ts

|- karma.conf.js

|- package.json

|- tsconfig.json

|... other files/folders

As you can see, there is a test folder where we can add our testing files. Just make sure to use the .test.ts extension for them.

The karma.conf.js file contains the configuration needed for testing with Karma. Why you should use Karma? In words of the open-wc team:

We recommend karma as a general-purpose tool for testing code that runs in the browser. Karma can run a large range of browsers, including IE11. This way you are confident that your code runs correctly in all supported environments.

Also, the package.json file defines the following scripts for testing:

{

"scripts": {

...

"test": "tsc && karma start --coverage",

"test:watch": "concurrently --kill-others --names tsc,karma \"npm run tsc:watch\" \"karma start --auto-watch=true --single-run=false\"",

},

...

}

Use the npm run test command for single running. And use npm run test:watch for running unit tests in watch mode(Enable watching files and executing the tests whenever one of these file changes).

Testing Libraries

The open-wc team recommends the following libraries for testing:

- mocha, as the testing framework running on Node.js and in the browser.

- chai, as the assertion library. It can be used with any other JavaScript framework today.

Along with them, there are a set of tools and helpers available:

- @open-wc/testing-helpers. a library with helpers functions for testing in the browser.

- @open-wc/semantic-dom-diff, which allows diffing chunks of DOM or HTML for semantic equality.

- @open-wc/chai-axe-a11y, which provides a Chai plugin to perform automated accessibility tests.

All these powerful tools are configured and available as a single package: @open-wc/testing. You don’t need to perform an additional step to start writing your tests!

Writing Unit Tests

If you’re following the Web Components with TypeScript series in the blog, you’ll find a fully functional project with Web Components implemented using LitElement and TypeScript.

Testing the About Page

This would be an example of a basic implementation of a Web Component:

import { LitElement, html, customElement } from 'lit-element';

@customElement('lit-about')

export class About extends LitElement {

render() {

return html`

<h2>About Me</h2>

<p>

Suspendisse mollis lobortis lacus, et venenatis nibh sagittis ac. ...

</p>

`;

}

}

Let’s create a file for its unit tests as /test/about.test.ts with the initial content:

import { LitElement, html, customElement, css, property } from 'lit-element';

import { About } from '../src/about/about';

describe('About Component', () => {

let element: About;

beforeEach(async () => {

element = await fixture<About>(html` <lit-about></lit-about> `);

});

});

Here’s the sequence of actions to understand what’s happening better:

describe('About Component')gives a meaningful description of the testing scenario.let element: Aboutdeclares a variable to contain a reference to the rendered Web Component. This variable will be available for the entire describe block.beforeEach()function runs as a set of preconditions before running the tests. In this case, it’s rendering the string provided as<lit-about></lit-about>and puts it in the DOM. This is an asynchronous operation and will return aPromise<About>- Finally, since we’re using

async/awaithere, the variableelementwill contain the expectedAboutcomponent.

At this point, we’re ready to start with the component testing. Add the following test right after beforeEach:

it('is defined', () => {

assert.instanceOf(element, About);

});

This test asserts that the element variable contains an instance of the About class.

Next, add the following it block to test the title rendering:

it("renders 'About Me' as a title", () => {

const h2 = element.shadowRoot!.querySelector('h2')!;

expect(h2).to.exist;

expect(h2.textContent).to.equal('About Me');

});

Here’s the sequence of actions explained:

it()function sets a test with a meaningful description for its purpose.element.shadowRoot!.querySelector('h2')!looks for a DOM node that matches the specified selector “h2”. That element should be part of the Shadow DOM, then, it’s required to do it throughelement.shadowRootcall.- The previous call can produce

nullas result(in case there’s no match with the selector). In TypeScript, we can use the non-null assertion operator(!). In other words, you’re telling the TypeScript compiler: “I’m pretty sure the element exist”. expect(h2).to.existis the formal assertion to verify thath2variable is notnullorundefined.- Next, there is an assertion about the text content for the provided selector

h2.

You can apply the same principles to validate the rendered paragraph:

it('renders a paragraph', () => {

const paragraph = element.shadowRoot!.querySelector('p')!;

expect(paragraph).to.exist;

expect(paragraph.textContent).to.contain('Suspendisse mollis lobortis lacus');

});

Testing the Blog Card Component

As you may remember, the Blog Card Component implementation is using LitElement too:

import { LitElement, html, customElement, css, property } from 'lit-element';

import { Post } from './post';

@customElement('blog-card')

export class BlogCard extends LitElement {

static styles = css`

// your styles goes here

`;

@property({ type: Object }) post?: Post;

render() {

return html`

<div class="blog-card">

<div class="blog-description">

<h1>${this.post?.title}</h1>

<h2>${this.post?.author}</h2>

<p>${this.post?.description}</p>

<p class="blog-footer">

<a class="blog-link" @click="${this.handleClick}">Read More</a>

</p>

</div>

</div>

`;

}

public handleClick() {

this.dispatchEvent(new CustomEvent('readMore', { detail: this.post }));

}

}

Let’s create another file for the unit tests as /test/blog-card.test.ts with the initial content:

import { assert, expect, fixture, html, oneEvent } from '@open-wc/testing';

import { BlogCard } from '../src/blog/blog-card';

import { Post } from '../src/blog/post';

const post: Post = {

id: 0,

title: 'Web Components Introduction',

author: 'Luis Aviles',

description: 'A brief description of the article...',

};

describe('Blog Card Component', () => {

let element: BlogCard;

beforeEach(async () => {

element = await fixture<BlogCard>(

html`<blog-card .post="${post}"></blog-card> `

);

});

});

There’s a lot in common with the previous test file. However, in this case, it’s needed to set a Post object to be sent as a parameter to create the <blog-card> component.

Let’s add some tests right after beforeEach function:

it('is defined', () => {

assert.instanceOf(element, BlogCard);

});

it('defines a post attribute', () => {

expect(element.post).to.equal(post);

});

The first test is about an instance assertion: Is this ’element’ an instance of BlogCard class?.

The second test goes a little bit deeper since it’s verifying the value of the custom element property post. Remember that property was defined using the @property decorator.

Now, let’s add some tests to verify the rendering of the different sections from our Web component:

it("renders 'Web Components Introduction' as a title", () => {

const h1 = element.shadowRoot?.querySelector('h1')!;

expect(h1).to.exist;

expect(h1.textContent).to.equal('Web Components Introduction');

});

it("renders 'Luis Aviles' as author", () => {

const h2 = element.shadowRoot?.querySelector('h2')!;

expect(h2).to.exist;

expect(h2.textContent).to.equal('Luis Aviles');

});

it("renders a 'Read More' link", () => {

const a = element.shadowRoot?.querySelector('a')!;

expect(a).to.exist;

expect(a.getAttribute('class')).to.equal('blog-link');

expect(a.textContent).to.equal('Read More');

});

There’s something new here: expect(a.getAttribute('class')). The getAttribute function will inspect the DOM and it will look for the class attribute. On the template side, it defines the link to Read More about the current blog post: <a class="blog-link">Read More</a>

Since <blog-card> is a reusable component, it would be useful to test the event propagation once it’s selected:

it('dispatch a click event', async () => {

setTimeout(() => element.handleClick());

const { detail } = (await oneEvent(element, 'readMore')) as CustomEvent<Post>;

expect(detail).to.be.equal(post);

});

setTimeout()function schedules a click action over the web component.- Next, the

oneEventfunction helps to handle and resolve the expected event named “readMore”. Once it’s resolved, we should expect aCustomEvent<Post>. - When a Custom Event is fired, you can expect to have a

detailattribute with an object. The Object destructuring would be useful in this case. - Finally, there’s an assertion to verify the detail value. It should be the

postset as an attribute for the Web Component.

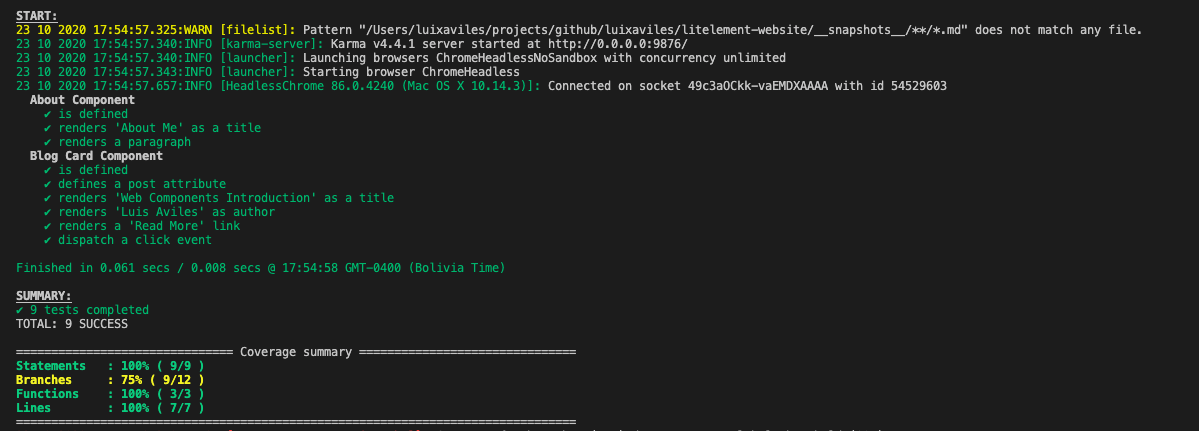

Running the Tests

Just run the following commands:

npm run test, a single running of the whole suite of tests.npm run test:watch, enable a watch mode. Especially useful to see the test results while you’re performing changes into the test files.

The output for the first command would be as follows:

Source Code Project

Find the complete project and these tests in the GitHub repository. Do not forget to give it a star ⭐️ and play around with the code.

You can follow me on Twitter and GitHub to see more about my work.